War is not a video game

November 25, 2015

Video game technology has made some amazing advances in recent decades. When I was 10 years-old, my mom got me my very first Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), and with that, came the Nintendo NES Zapper, a grey, plastic gun used for the game, Duck Hunt. I was very good at Duck Hunt, and I really enjoyed it when the Basset Hound would stick his head up from the weeds with a dead duck in his mouth. If I missed my target, the same dog would rise up slowly, and chuckle at me with his paw over his mouth, in a sort of condescending way.

When I was a teenager, and I was finally able to afford the second installment of the NES series, a Super Nintendo, my favorite game was Killer Instinct, a graphic fighting game that took the player through a series of opponents. I have never been a fanatic about video games. When I got the original NES, my friends were playing on the Super Nintendo. When I got a Super Nintendo, everyone else was playing the Nintendo 64, and so on, and so on. Always being a step behind, I was never in a position to fully embrace the magic of the gaming culture. Things have certainly changed.

Imagine you are sitting in what looks like a flight simulator; you have a joystick, a computer screen, and a mission plan. You are in a full flight suit, so that you can “really feel like you’re in a war,” and really put your head in the game. You have 18 targets today, and you are confident that you will make your quota. One by one, you eliminate each of your targets, with a quiet “Hoo-Ra!” You follow through on each phase of your plans, with as much precision as you are capable, given the crude pixilation on the screen before you, and you are certain that you are still at 100% health, however, you cannot say the same for your “targets.” In fact, you cannot even say whether you hit only your target, or more than your target, because, in your simulator-like station, there is no ground contact, so knowing what the collateral damage is deemed classified, need-to-know- information.

You have had another successful day in pseudo-cockpit, and now it is time to head home. You walk in to your quaint, 4-bedroom house, say hello to your spouse, kids, and that lovable mutt your daughter wanted. You sit down for dinner; ask your oldest how his math homework is going, and all is right with the world, except… except that your Reaper, which can carry thousands of pounds of “payloads,” resulting in high collateral damage, just leveled a building, and you know that your accuracy rate is less than 5 percent. Actually, it is somewhere between 1.5 and 2 percent accurate, and one-eighth of everything you hit, has the potential of being children.

“The smoke clears, and there’s pieces of the two guys around the crater. And there’s this guy over here, and he’s missing his right leg above his knee. He’s holding it, and he’s rolling around, and the blood is squirting out of his leg, and it’s hitting the ground, and it’s hot. His blood is hot. But when it hits the ground, it starts to cool off; the pool cools fast. It took him a long time to die. I just watched him. I watched him become the same color as the ground he was lying on.”

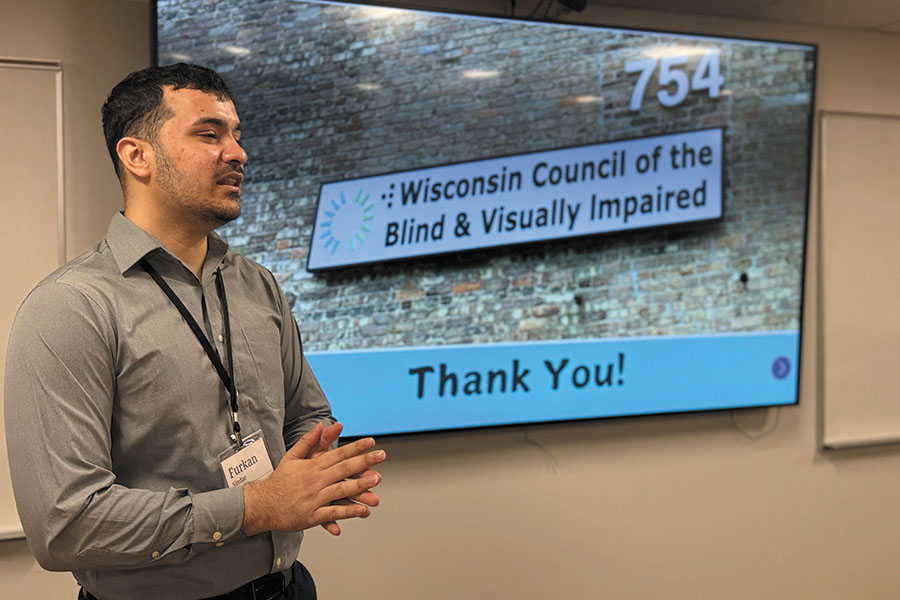

That is a quote from the GQ Magazine article, “Confessions of a Drone Warrior,” by Matthew Power, in which Airman First Class Brandon Bryant recounts his first “shot” in the cubicle-like cockpit, or Ground Control Station (GCS) at Nellis Air Force Base located on the outskirts of Las Vegas. It was there that Bryant carried out his duties as a remotely-piloted-aircraft sensor operator, known to soldiers as a “sensor” for short, and part of a U.S. Air Force squadron that flew Predator drones over Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the six years that he served in the United States Air Force as a Sensor, Bryant never left Nevada. Each day he would put in his hours at the bland Army base warehouse, and each evening he would return to his home.

“I kind of finished the night numb,” Bryant said. “Then you just go home. No one talked about it. No one talked about how they felt after anything. It was like an unspoken agreement that you wouldn’t talk about your experiences.”

It is true that soldiers, before returning to home from any active combat, are given the choice to debrief on the activities, and many decline to do so. There is speculation why anyone would choose not to participate in counseling after such moral, ethical decisions have been made. My feeling is that military teaches soldiers how to view and experience their combat, and talking about it with certain people is not favored.

On the one hand, data supports that doing something in the virtual world will feel “real” to an individual who is plugged in, and yet, those who advocate for virtual soldiers say that their men and women understand the difference between the two. How can this be possible? While engaged in actual combat, through virtual experience or not, will these soldiers own the psychological, emotional capacity to embrace the real consequences of their actions?