Indigenous Kitchen

Sean Sherman: chef, forager, Native American, and ready to change the world’s mind

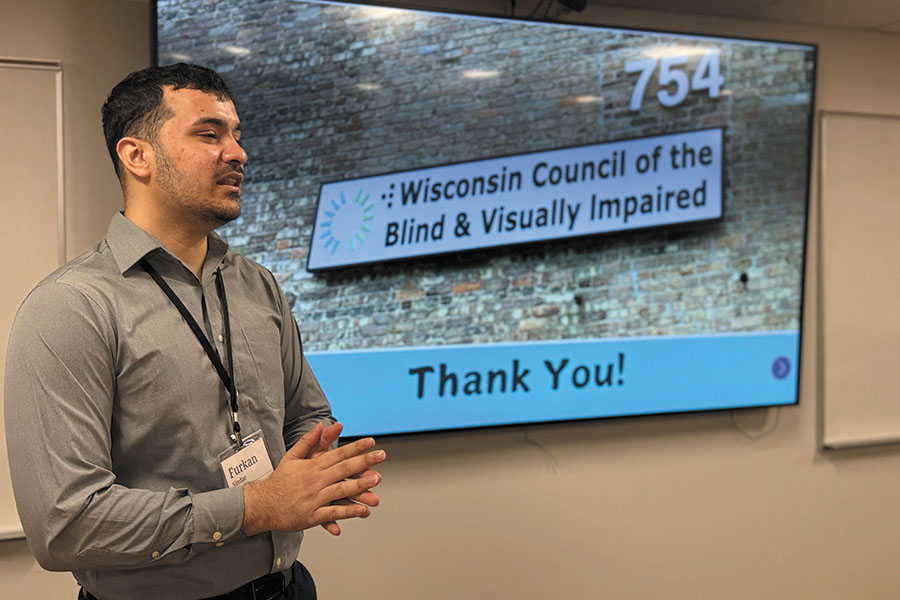

Chef Sean Sherman, left, joins host Kyle Cherek at Madison College’s Chef Series event held on Feb. 13 at the Truax Campus

February 19, 2019

Madison College’s Chef Series featured award winning Chef Sean Sherman on Feb. 13 at the Truax Campus.

Sherman has spoken on NPR, been a presenter at the UN, and won the James Beard award, a coveted prize for chefs across the nation.

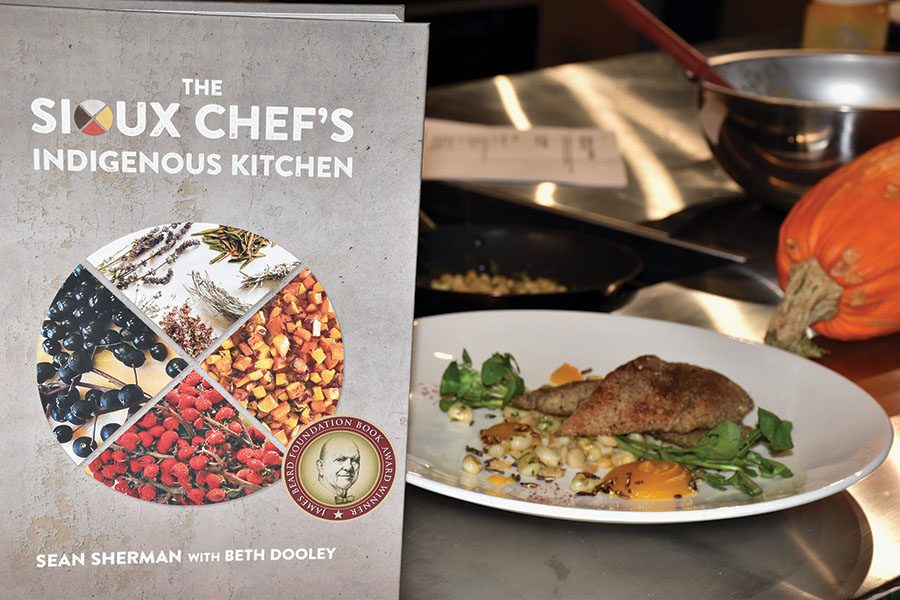

His cookbook, “The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen,” was awarded the best cookbook in America in 2018.

Even better than his remarkable achievements is his mission to help grow knowledge of the plants and sustainable way of life lived by early Native Americans, and help present-day natives build careers in the culinary field.

Sherman was an unforgettable guest of Madison College’s Chef Series.

Native American born and raised on a South Dakota reservation, Sherman began working in kitchens at age 13. He taught himself traditional French cuisine, but soon realized how much food he wasn’t utilizing right in his own backyard. Armed with a passion for cooking and determined to find a more sustainable way of eating, Sherman began doing investigative research, and taught himself how to forage and cook like his pre-colonial ancestors.

Almost everything outside is edible, Sherman notes, and weeds are just names we give to the plants we don’t know what to do with. Traditionally, Native Americans would use plants for food, medicine, and construction or clothing. Knowledge of many plants allowed the early Native Americans to eat hundreds of varieties. Today, most of us eat only about 20-30 of the same types of fruits and vegetables that we buy at the store – despite all of the free food we have in our backyards. Sherman notes that the diverse diet of early Native Americans was much healthier than the narrow patterns of eating we follow today.

When preparing for his cooking, Sherman will harvest what is in the backyard of wherever he is in the country to assure the ingredients he is working with are fresh and grow in the region. Before his demonstration at the Chef Series, Sherman found branches of cedar outside on campus, and prepared cedar tea for members of the audience. Evergreens are one of the only plants you can forage during the cold Wisconsin and Minnesota winters, and he didn’t let the opportunity go to waste. The tea, made with local maple syrup, tastes like the forest, he said.

It seems that many people have a fear of foraging. Perhaps we’ve all watched a few too many movies that feature poison berries. However, Sherman assured the audience that with proper research, foraging is not only safe, but extremely healthy.

Sherman believes we have lost touch with our knowledge and connection to the earth. He thinks chefs should all have an ethnobotanist in their kitchen to guide them to cook with all different varieties of plants. “It’s easier to teach an ethnobotanist to cook than to teach a cook ethnobotany,” laughs Sherman.

Foraging provides access to a bounty of free food. “We should have enough wild rice to feed everyone,” says Sherman. He believes we have enough food grown locally that we can avoid imports to create a healthy, local lifestyle. He adds that we need to bring back the old cooking traditions created in our own country.

In addition to his expert chef skills, Sherman is enthusiastic about an organization he started called NATIF. NATIF, or Native American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems, is a non-profit organization started by Sherman to teach classes to share knowledge of cooking and foraging to both Native American communities and anyone else interested.

Easily, Sherman could have started a restaurant in Minneapolis where he now lives, create phenomenal food and stop there. But he decided to take his mission a step further and reach people across the nation. Sherman has set up bases for classes across several reservations in America, each one tailored to the food grown in that specific region. Sherman believes a reconnection with our food will help solve not only our food and health problems but will also provide countless opportunities for Native Americans.

“I want to give back,” says Sherman. “Growing up on Pine Ridge where still today over 70% of the population lives in poverty – meaning they make less than $6,000 a year for the family – there’s a lot of work to be done, and there could be a lot of opportunity for native chefs and young native kids to come and do this kind of work. We’re hoping to create a situation to help grow this and help push it into a healthy future.”

During his demonstration at the Chef Series, Sherman prepared white fish harvested locally in Wisconsin, and signed cookbooks for audience members which immediately sold out. Though Sherman has a right to be proud of his achievements, his passion comes from an innate desire to make the world a better place for everyone. “I’m happy to be a voice,” he says, but his mission is much larger than himself.