Addressing the harms of censorship, speaker discusses impact of ongoing efforts to ban books

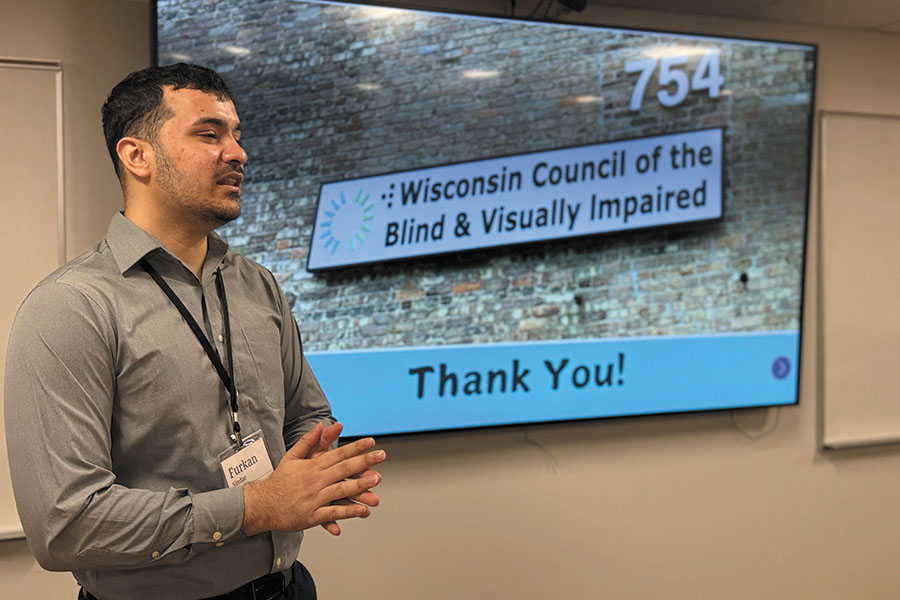

Emilo DeTorre, director of community engagement for the American Civil Liberties Union of WIsconsin, speaks about banned books and censorship during a presentation at Madison College on Sept. 26.

October 11, 2017

Every autumn in late September, as students are returning to school, the American Library Association dedicates one week to raise awareness of the harms of censorship – an event called Banned Book Week.

To celebrate the event this year, Madison College’s Yahara Journal welcomed Emilio DeTorre, director of community engagement for the American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin (ACLUW), to campus to speak about “Banned Books and Censorship.”

During the conversation DeTorre touched on topics ranging from modern trends in the banning and challenging of books to specific instances of books being and challenged currently across the United States.

He said in the past 10 to 20 years, the banning and challenging of books has moved from the federal and state level to local institutions, such as county school boards and local libraries, and how this change has made the work of the American Library Association and the American Civil Liberties Union much harder. Activities by small institutions and especially in small municipalities will often not be publicized and go unnoticed. The American Library Association estimates that currently 82-97 percent of book challenges go unreported.

DeTorre also discussed the most common reasons that books are challenged. On the surface, the top three reasons groups or individuals ask for books to be removed from libraries are that they contain sexually explicit material, offensive language, and or are unsuited for the intended age group. But as DeTorre states, the broad and subjective nature of these terms is a cover for objecting to books based on themes such as race, religion, gender, and sexuality.

During his discussion, DeTorre pointed to recent instances in Texas and Arizona that have brought the debate of book banning into the public spotlight. In the Unified Tucson School District of Arizona, which serves roughly 47,670 students, 61.3 percent of whom are Hispanic, the district attempted to ban a Chicano Studies program as well as remove literature from its library that was deemed “Anti-American.”

In Texas, controversy has also been sparked recently when school boards sought to change textbooks as to not use the word “slavery” and replace it with “workers,” “imported laborers,” or “forced laborers.”

Following the event, DeTorre and his colleague, Molly E. Collins, the Associate Director of the ACLUW visited with The Clarion.

Clarion: In your opinion, what are some of the most important works of literature that have been banned or have been challenged?

DeTorre: Well, “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” But I think it’s less a matter, for me, it’s less which individual book has (been challenged) and which is the greatest crime of attempting to deprive and censor the largest audiences. When you take a look at Arizona, where they tried to rewrite and deprive millions of people of knowing about their own heritage and identity, that’s disgusting.

So it’s even less just a book, it’s what they’re trying to steal from these folks. When you see Texas trying to rewrite that slavery existed in the United States and trying to soft-sell that. That’s a disgusting crime. And I think that’s more poignant than, “Oh I’m going to remove this one book.” That’s an attempt to wholesale reprogram or brainwash an entire population.

Clarion: What is the danger of whitewashing the past? What do we lose when we whitewash the past?

DeTorre: Well it means we’re building our future on a lie. We’re depriving ourselves of the truth. We can’t make informed decisions if we don’t have all the facts. You know, we’re going to repeat the mistakes of the past if we haven’t learned that other people have been down here before.

Collins: We can’t get to a point where we’re actually having a real conversation about race and racism if we are not looking at the historical place that all comes from.

Like you cannot talk about the current state of mass incarceration in this country without talking about slavery, the slave codes, the way the systems of policing were built to keep black people in a certain place.

We’re never going to get past that. We’re never going to grow if we don’t think about these issues in a real way. And we haven’t even been doing a good job in our current textbooks. But if we change “slavery” to “laborers” or “import laborer” then we can’t have that honest conversation.

DeTorre: I think sometimes people try to do that intentionally. They’re not admitting that the problem exists and they’re going to remove the evidence so that they can further admit that there is no problem.

Clarion: In your experience, what ideas or types of ideas are most in danger of being targeted by censorship?

Collins: Race and sexual minority. LGBT. Religion.

Clarion: In the presentation it said the most frequent reasons that books are banned is because of sexually explicit, offensive language, and or being unsuited for age group?

Collins: The definitions of those things though are highly subjective. When parents challenge the book “Looking for Alaska” because there’s a discussion in the book. They talk about (oral sex). It’s the least sexy description of sex ever. But that’s too graphic for them (critics of “Looking for Alaska”) just that it exists in the world and that a high school student might hear (about it). The whole context in the book is talking about how if you’re not ready, if you’re not into it, this isn’t fun. So if you’re a parent whose thoughtful about it you can have that conversation. You can use it to teach your kid: maybe you should wait, because maybe you’re not ready. But you don’t give the kids that language if you try to keep the idea from them.