Nurse shares experience battling Ebola

October 14, 2015

Last year, countries in West Africa were devastated by the world’s longest and largest Ebola outbreak in history. Liberia had it the worst, hitting it’s peak from August to September 2014, where 300 to 400 cases were reported every week. Before the outbreak began, Liberia had only 60 doctors to treat its entire population of over four million, but response from local volunteers and international organizations helped.

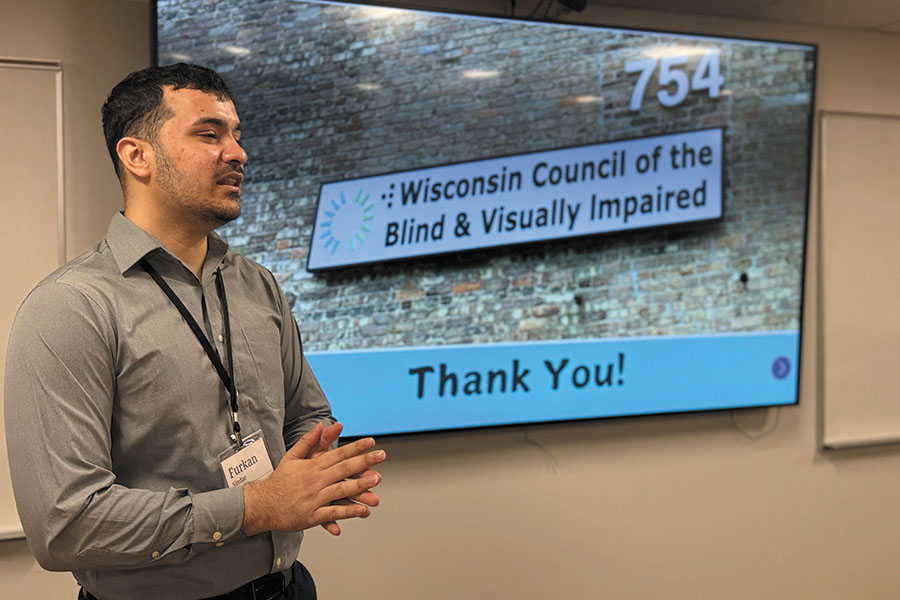

Among the international aid was emergency room nurse Marc Rosenthal, who took a leave from his job in Madison to volunteer at a health clinic in Sierra Leone, the second most devastated country in the outbreak. Coming to Madison College to speak about his experience on the field last Tuesday, Oct. 6, Rosenthal relived the devastations and struggle he faced in Sierra Leone.

In Sierra Leone, pre-Ebola, the life expectancy was a short 45 years. Adequate medical facilities plummeted as 400 medical workers died within the first few months of the outbreak. Medical specialists and volunteers had to work with the limited resources, lacking tourniquets and IV poles, and using duct tape to keep the IV’s in place.

When working directly with affected patients, nurses could only work for 90 minutes at a time due to the heat combined with the heavy protective garb they wore, including boots, three pairs of gloves, and a full body suit.

Almost 12,000 people were killed by Ebola, with nearly 30,000 total being affected, although considering the difficulty in collecting data, these numbers are just estimates.

One of the biggest challenges faced in the countries affected were cultural barriers. With Sierra Leone being a predominantly Muslim country, many believed that the body will be cursed if not washed, wrapped, and buried in adherence to Islamic custom. With a virus as transmissable as Ebola, safe burials to avoid further infections were critically dependent on communities cooperating. Yet, Rosenthal remembered family members unburying the deceased in order to give them a proper burial.

“One day, an infected family of 13 walked into the clinic, and it was because they had to decided to unbury their [deceased loved one],” Rosenthal explained.

It’s important for nursing students, who were the main attendees at Rosenthals talk on Tuesday, “to be aware of the need for this type of specialized training”, says Dr. Mara Eisch, Nursing Faculty at Madison College. “[Things like this] could pop up anywhere, anytime,” and students need to be cognizant of how to triage and perform under limited resources, she explains.

“You could just see how passionate he is about what he did as he spoke, about nursing, and [his talk] really opened students eyes to things that they wouldn’t have thought of before as nursing students, things that aren’t learned in the curriculum but are important for future jobs, roles, or development,” Eisch explains.

Eisch also mentioned that due to the Nursing degree following a statewide curriculum, there isn’t much room for adding or changing content, such as incorporating classes or seminars that include introduction to cultures and customs of different countries.

If international volunteers arriving on the scene in affected countries were fully informed of the traditions of each country, perhaps the escalation of the virus could have been apprehended more quickly, with more community involvement and understanding, which, according to WHO, is the most important factor of battling the virus.

If communities aren’t aware of basic hygiene skills and already lack proper medical facilities, well-intentioned medical volunteers covered from head to toe in foreign equipment won’t ensure quick community involvement.

Being a short 2-year nursing program, it’s not feasible to include everything “in the heart of nursing as a discipline” into the curriculum, Eisch explains.

Despite only being in Sierra Leone for a few months, Rosenthal was able to be a part of a small medical team in his region that increased the survival rate from 10 percent to 40 percent, with a focus on electrolyte and fluid restoration and rebalance.

Last month, on Sept. 3, the WHO declared Liberia free of Ebola virus transmission, the last of the three countries most highly-affected. While it may be easy for Ebola to come back, the world will continue to keep an eye out on West Africa to promote social, emotional, and medical health after the devastating effects Ebola had on those regions.