Funding concerns follow free tuition proposal

February 3, 2015

Aboard Air Force One, in the weeks prior to his State of the Union Address, President Obama announced his plans to speak on a proposal for free tuition to two-year community colleges. On Jan. 9 the White House released a fact sheet with the President’s plans calling it America’s College Promise (ACP), and in the address said that he wants to make two-year college as free and universal as high school.

The fact sheet draws on data from the nation’s current student populace, stating that “40 percent of college students are enrolled in more than 1,100 community colleges throughout America.” These colleges strive for affordable tuition, open admission policies, and convenient locations. It also claims that at least 35 percent of job openings in this new economy will require some kind of bachelor’s degree and 30 percent with some form of an associate’s.

The prospect of attending two years of college with a waived tuition sounds incredible. Society significantly benefits from quality education being affordable for everyone. As tuition prices continue to climb along with the cost of housing, food, and transportation, the financial burden of attending even a two-year college is too much for many. Those who are extremely economically disadvantaged might consider higher education virtually impossible.

The White House’s fact sheet outlines what they plan for America’s College Promise, wherein lies a host of affirmatively titled plans that call our legislators to action, and offer opportunity and expansion.

Tax policy is complicated and enigmatic at best. However, we as students are aware that through grants and other subsidies funded by the federal and state governments, we can afford to go to school with much of the burden of tuition relieved from our shoulders.

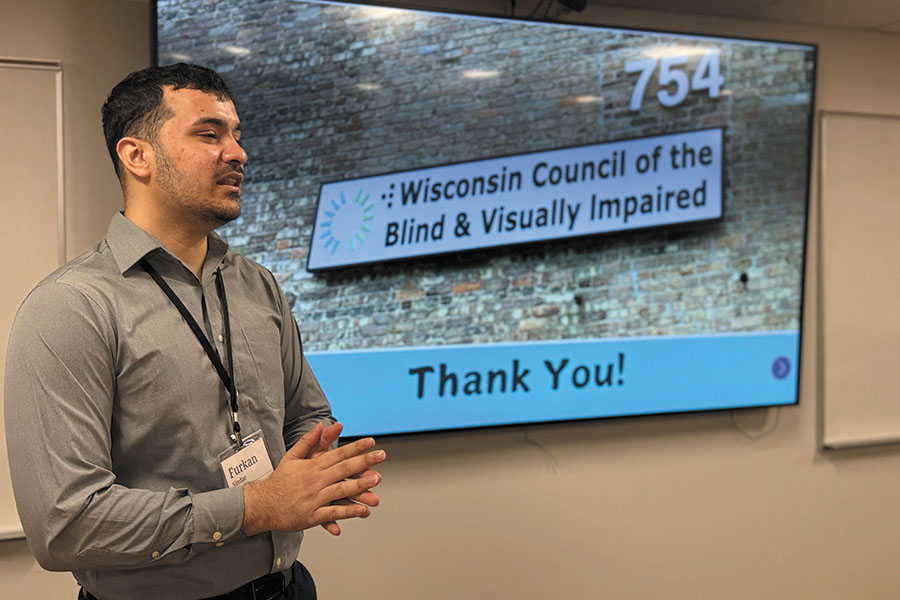

Madison College president Dr. Jack E. Daniels’s initial reaction to the proposal was that it would be a great way to open access to students who may have not had an opportunity in the past, but he proceeds with caution.

“I mean, how do you fund those types of programs? I think it’s important to look at that funding,” said Daniels.

He explained that with programs like Tennessee’s Promise, which is used in part as a model for a proposal, students would use their Pell Grant with the remainder paid for by the state; with Tennessee using the money from their state lottery.

It is important to look at funding, especially when funds are coming in through corporate or private donations, which may come with strings attached. For example, in 2011 the Charles Koch Foundation considered giving over a million dollars to the Florida State economics department, it would have required the school to teach libertarian deregulatory economic philosophy, and accept the authority of a Koch-appointed advisory committee on hiring and performing evaluations.

There are stipulations that come with America’s College Promise.

“When you look at some of the parameters, like requiring a 2.5 GPA … but also if they put that 75 percent from the feds to cover that tuition cost, then the states would have to step in for the remainder of it,” said president Daniels when asked about the likelihood of such a proposal becoming a bill and becoming passed. “It’s up to the states to opt in on covering the remainder in some other way.”

For states that opt out of covering the other 25 percent, they would not be allowed to participate in the program at all. If it ever does, between now and the time it takes for the program to become law, it would be up to the Wisconsin Technical College System’s Presidents Association to work with legislators.

Daniels’s job, he says, is to “stake out the case for funding […] I probably meet with our local legislators at least quarterly.” And as part of Madison College’s policy of shared governance, there is currently one student on each of the advisory committees to ensure our schools voices are heard.

Said Daniels on America’s College Promise, “I think the chances of it passing are slim.”